Jacob A. Riis: The Camera vs. Social Injustice

By ARTHUR H. BLEICH

Images by Jacob A. Riis

Newly arrived immigrants to New York City during the late 1800s quickly found that rumors they night have heard about the “Promised Land” were just that; the streets of America were not paved with gold.

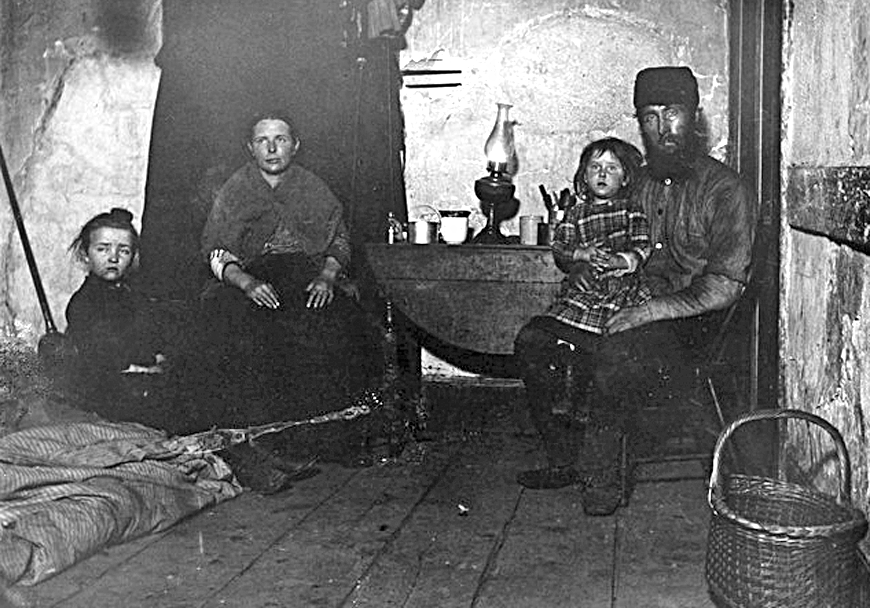

In fact, if you were poor, just finding a place to sleep was incredibly difficult. Filthy, unhealthy and overcrowded tenement housing was the norm, but bad as that was, it was still better than having to sleep under bridges, in alleys or cemeteries as many were doing.

In 1870, Jacob Riis (pronounced “reese”) decided to leave Denmark and head for America. He had just turned 21, came from a good family and had been a carpenter’s apprentice until he’d asked for the hand of his boss’ daughter three years earlier. Not surprisingly, he was fired— the girl was only 12 and her father was furious that Riis would have the audacity the to ask to marry so young a girl. After his discharge, he found the job market in Denmark was not very promising and so, in 1870, Riis sailed for New York City to try his luck in a new land.

He’d learned English when he was growing up which was big plus and, after trying his hand at several different occupations, he gravitated toward the newspaper business and was hired by the New York Tribune as a police reporter. There was no dearth of material for him to write about—his beat covered the infamous Lower East Side of Manhattan.

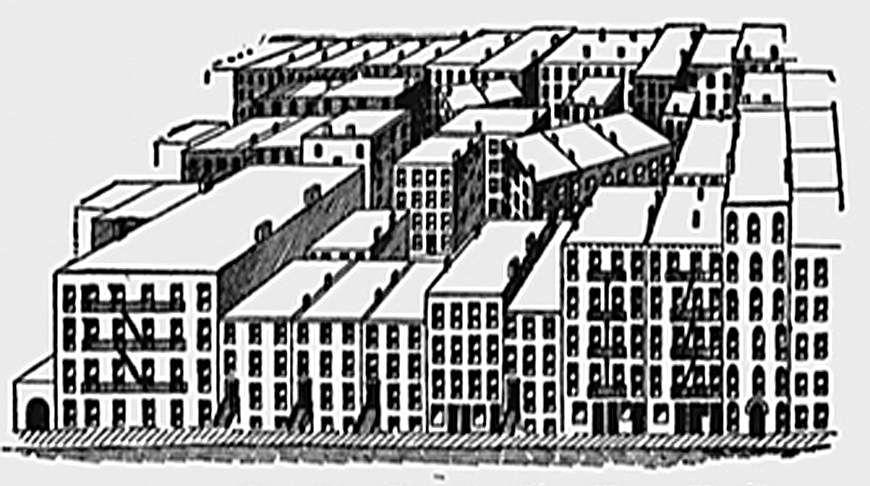

By the 1880’s more than 334,000 people lived within a square mile in that area, most of whom were crammed into claustrophobic tenement housing, 10 or 15 to a room. Riis soon found that in the more refined circles of citizenry, the immigrants were simply regarded as “wretched refuse” a description coined by Emma Lazarus in her poem “The New Colossus” which celebrated America’s Statue of Liberty. But Riis looked at them as vital contributors to the future of a great nation. Deeply disturbed by their plight, he began to think about what he might be able do about it

Whenever the poor had been the subject of newspaper articles, the story was usually accompanied by sketches that Riis felt failed to adequately depict the realism he encountered in his everyday reporting. In fact, it took until 1880 before New York newspapers were able to publish photographs at all, using the newly developed halftone process. And though photography had begun to come into favor, Riis rejected it because lenses were slow and films were not very sensitive to light. It could not go into the dark and squalid places people lived in and produce suitable images.

But in 1887 Riis was excited to learn that that "a way had been discovered to take pictures by flashlight. The darkest corner might be photographed that way." Flash powder, a mixture of magnesium and two other compounds had arrived— an invention by two German photo enthusiasts. The mixture was placed in a bullet-like shell and fired with a special gun. As the process was refined, the gun, which looked threatening, gave way to a pan -like receptacle. Taking a photos using it was simple: set the camera up on a tripod, remove the lens cap, ignite the flash, and then replace the lens cap.

One of Riis’ friends, an avid photographer, suggested that he purchase his own equipment and in January 1888, Riis paid $25 for a 4×5 box camera, plate holders, a tripod and equipment for developing and printing. In today’s money it was an investment of more than $700— more than a year’s wages for some workers at that time. He took his new camera to a local cemetery to practice, making two exposures. The results were seriously overexposed, but successful. After that, he was hooked.

Working on his beat at night, he was able to capture all the repulsive aspects of the slums; dark streets, cramped tenement apartments, disreputable saloons, and also document the abject poverty in which the immigrants lived. And though photo reproduction in publications was still not common, the drawings made from his photographs were far more realistic than previous ones. Eager to have people see his original photogaphs, Riis organized magic lantern shows where he projected them to the amazement of fascinated audiences.

Riis eventually published a book that included his photographs titled "How The Other Half Lives.” Reviewed in the New York Times on January 4, 1891, it offered insights into how the photographer worked. “Mr. Riis’s views of the conditions of “the other half” my not be sentimental but rather the insight of one of a practical turn of mind who describes exactly what he sees. He goes into the slums with his camera and flash light and in his illustrations he presents what the photograph has produced on the plate. It has been often black and dark where he has gone that only the magnesium wire would clear up the scene.”

His photographs were so powerful that it motivated the government to form a Tenant House Commission in 1884 that began to to take action against slum landlords and this encouraged Riis to expand his his social documentary forays to other parts of New York A particularly rewarding effort by him was his exposé of the condition of New York's water supply. His five-column story "Some Things We Drink” published in the August 21, 1891, edition of the New York Evening Sun, included six photographs (later lost).

Riis described his trip to the upstate reservoir : "I took my camera and went up in the watershed photographing my evidence wherever I found it. Populous towns sewered [dumped sewage] directly into our drinking water. I went to the doctors and asked how many days a vigorous cholera bacillus may live and multiply in running water. About seven, said they. My case was made." The story resulted in the purchase by New York City of areas around the New Croton Reservoir, and may well have saved New Yorkers from an epidemic of cholera.

Throughout his life, Riis was a crusader for the betterment of conditions for the impoverished people of his time. Today, a beautiful New York City seaside recreational park commemorates his service to his beloved city. He died at the age of 65 on May 26, 2014 and will be remembered as one of the early practitioners of social documentary photography.

Original Publication Date: September 17, 2024

Article Last updated: September 18, 2024

Related Posts and Information

Categories

About Photographers

Announcements

Back to Basics

Books and Videos

Cards and Calendars

Commentary

Contests

Displaying Images

Editing for Print

Events

Favorite Photo Locations

Featured Software

Free Stuff

Handy Hardware

How-To-Do-It

Imaging

Inks and Papers

Marketing Images

Monitors

Odds and Ends

Photo Gear and Services

Photo History

Photography

Printer Reviews

Printing

Printing Project Ideas

Red River Paper

Red River Paper Pro

RRP Products

Scanners and Scanning

Success on Paper

Techniques

Techniques

Tips and Tricks

Webinars

Words from the Web

Workshops and Exhibits

all

Archives

January, 2025

December, 2024

November, 2024

October, 2024

September, 2024

August, 2024

July, 2024

June, 2024

May, 2024

more archive dates

archive article list