Jack Delano’s Greatest Photo Assignment

by Arthur H. Bleich–

Jack Delano’s fascination with trains began when he was eight, but it wasn’t until he was nearly 30 that he got a photographer’s dream assignment: Document the nation’s railroads in time of war. The year was 1942.

Delano (pronounced de-LAY-no) was born Jacob Ovcharov on August 1, 1914 in the small village of Voroshilovka in the Ukraine. His teacher father and dentist mother exposed him to music and art at an early age, setting the scene for his later interest in photography. In 1923 his family embarked on a railroad journey –exciting as it could get for a young boy– through Russia, Latvia, and Germany on the way to a new life in Philadelphia.

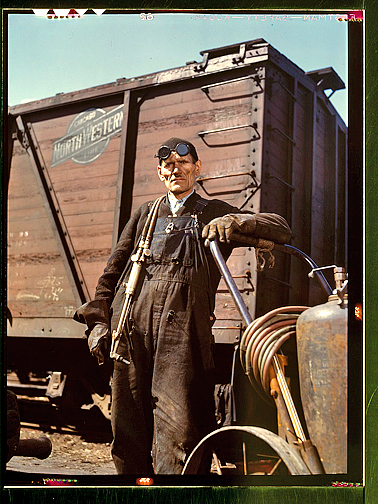

Mike Evans, a welder, at the rip tracks at Proviso yard of the C & NW RR [i.e. Chicago and North Western railroad], Chicago, Ill.

After graduating from art college in 1937, Delano worked as a photographer for the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and his coverage of the lives of poor coal miners eventually brought him to the attention of Roy Stryker, head of the Farm Security Administration (FSA). Stryker invited him to join an elite group of photographers who criss-crossed the country documenting government projects set up to improve the lives of the nation’s farmers and workers. A friend had previously suggested that Jack (he had already chosen a new first name) pick a last name that sounded more American and so, in 1940, it officially became Delano.

After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, The FSA and its photographers shifted their emphasis to the war effort. In 1942, the agency became part of the Office of War Information (OWI) and the photographers swung into high gear as they were sent throughout the country to shoot pictures of military bases, factories, and farms that would appear in publications and exhibits both in the U.S. and abroad. Delano, to his delight, was assigned to document the railroads.

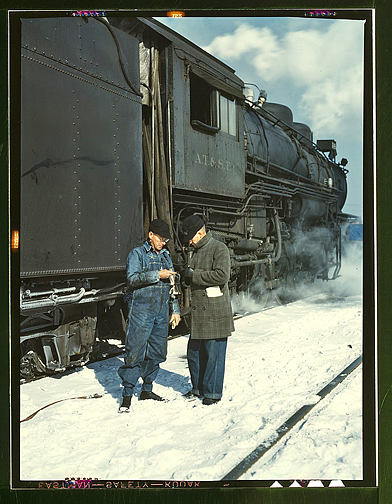

Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe railroad conductor George E. Burton and engineer J.W. Edwards comparing time before pulling out of Corwith railroad yard for Chillicothe, Illinois; Chicago, Ill.

In Photographic Memories (Smithsonian Press, 1997), Delano recalls that: “I was armed with credentials from the FBI, the Association of American Railroads, the Headquarters of the Western Defense Command, and the War Department Office of the Chief of Transportation.”

Starting in the Midwest Delano would eventually spend a month aboard freight trains riding with the crews both in the caboose and the locomotive and he even had the authority to stop a train (with the engineer’s consent) for any shots he wanted.

Most pictures shot by the OWI during WWII were in black and white, but a limited amount of a new color film, called Kodachrome in 4×5 inch size was made available to Delano and other OWI photographers. Many of them were wary of the new medium but not Delano. He plunged right in and shot over 500 pictures with it even though it was sometimes difficult to use because at an ASA (called ISO today) of 10, it was five to ten times less sensitive to light than most black and white films of the time and required longer exposures to get usable images.

Mrs. Viola Sievers, one of the wipers at the roundhouse giving a giant “H” class locomotive a bath of live steam, Clinton, Iowa. Mrs. Sievers is the sole support of her mother and has a son-in-law in the Army.

The fact that Delano would even attempt to shoot Kodachrome in the dingy interiors of repair shops, roundhouses, and stations or even at night in the yards, shows that he was an experimental camera artist, eager to capture the true colors of mid-20th-century America railroading. What’s more amazing is that the color photos of the FSA and OWI – about 1,600 in all– lay forgotten for nearly 40 years before they were discovered in 1978. Since they’re in the public domain, you can view them all, download those you like, and print them for you own collection. [see Resources below.]

But back to Jack Delano. After his work was done in the Midwest, he boarded a freight for a 2,000 mile trip on the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad. “At every stop,” he remembered, “I would hop off the train and photograph whatever I could, depending on the time available– the work in roundhouses and repair shops, where many women were employed, in switching towers, and in the trainmen’s living quarters.”

Workers at the roundhouse of the C & NW RR [i.e. Chicago and North Western railroad] Proviso Yard, Chicago, Ill.

At one of his stops he posted a letter to Roy Stryker in Washington, part of which said: “One of the first things I learned was that I couldn’t be in two places at the same time, that is, at the caboose end and at the engine end. The distance might be anything from a quarter of a mile to over a mile and it was impossible for me to be running back and forth because the stops were often very short and the train would start before I got to either end.”

Delano remembered that as the trip went on, he became more savvy, but even though he lost his fear of being left behind by learning to jump on the caboose as the train was moving, he still handed the brakeman his camera to take aboard because he needed both hands to hop on. He told Stryker: “Once in the caboose I learned another lesson from bitter experience: don’t stand up in a caboose unless you hold on to something, otherwise you and your camera might go flying out through the rear end of the train.”

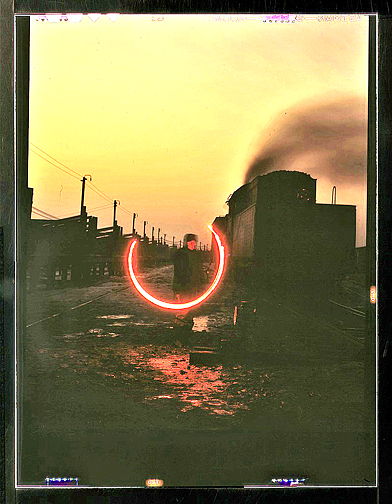

Indiana Harbor Belt RR, switchman demonstrating signal with a “fusee” – used at twilight and dawn – when visibility is poor. This signal means “stop.” Calumet City, Ill.

One day as he rode in the locomotive of a freight as it struggled to haul a hundred cars of war materials –bombs, tractors, trucks, mines, and military tanks– through the Arizona hills, Delano decided to exert his authority to stop the train for a dramatic picture. The engineer quickly put him straight. “Young man, if I stopped the train here we could never get started again but would go rolling down the hill backward.”

Undaunted, Delano waited until he was on a different train traversing the flat Nevada desert to get just the shot he wanted– the train rounding a curve with more than a hundred cars strung out a mile behind the engine. When he made his request this time, the engineer complied. Delano described the incident in great detail and with obvious relish.

“As he [the engineer] applied the brakes I could hear the clackety-clack go from car to car through the entire length of the train.” Once stopped, Delano hopped off and set up his 4×5-inch press camera on a tripod only to find that the composition wasn’t quite right– the train needed to go forward some more. He remembered shouting to the engineer to move the train up and again heard the clackety-clack as each car inched forward.

Women workers employed as wipers in the roundhouse having lunch in their rest room, C. & N.W. R.R., Clinton, Iowa.

“Never had I had such a sense of power,” he recalled. “I felt like Hercules. Wow! To think that I could move that whole train with just the wave of my hand!” When the shot was framed to his satisfaction, Delano signaled the engineer to stop and then exposed a few sheets of film. Finally, he waved the engineer to get going again and hopped on the caboose when it rolled by.

Jack Delano completed his assignment and went on to do many other photographic projects. He died August 12, 1997 at the age of 83, having left a legacy of thousands of black and white and color photographs taken for the government during tough times and better ones. But nowhere did his work shine more than in his color shots of America’s railroads in wartime. He put his all into that assignment, and it really shows.

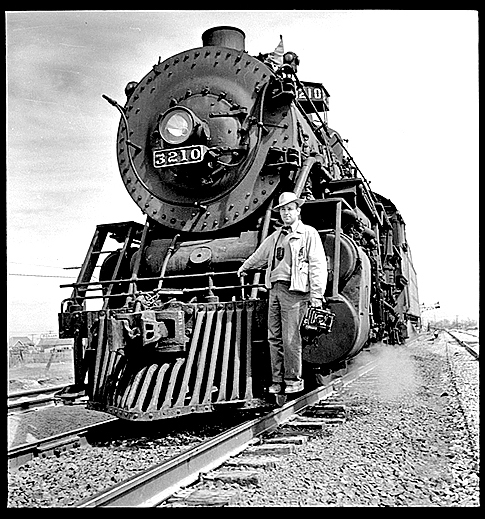

Jack Delano poses on the cowcatcher of a steam engine with his 4×5 Graphic camera in hand. All previous captions under his images in this article were written by him in 1942.

RESOURCES

To view and download free color (and B&W images) from WPA, FSA, OWI and other archived government files click here.

To purchase Photographic Memories by Jack Delano visit Amazon

To subscribe to Red River Paper’s newsletter, click here.

Original Publication Date: May 21, 2018

Article Last updated: May 21, 2018

Related Posts and Information

Categories

About Photographers

Announcements

Back to Basics

Books and Videos

Cards and Calendars

Commentary

Contests

Displaying Images

Editing for Print

Events

Favorite Photo Locations

Featured Software

Free Stuff

Handy Hardware

How-To-Do-It

Imaging

Inks and Papers

Marketing Images

Monitors

Odds and Ends

Photo Gear and Services

Photo History

Photography

Printer Reviews

Printing

Printing Project Ideas

Red River Paper

Red River Paper Pro

RRP Products

Scanners and Scanning

Success on Paper

Techniques

Techniques

Tips and Tricks

Webinars

Words from the Web

Workshops and Exhibits

all

Archives

December, 2024

November, 2024

October, 2024

September, 2024

August, 2024

July, 2024

June, 2024

May, 2024

April, 2024

more archive dates

archive article list