Josef Hoflehner: Images of Frozen History

By Arthur H. Bleich

The penguin had been resting peacefully, face up on the table for nearly a hundred years—a sleeping beauty never to be awakened by a kiss, frozen in time by the sub-zero Antarctic chill in an abandoned, soot-filled explorer’s hut.

Josef Hoflehner–one of the world’s renowned fine arts photographers– and his daughter, Katharina, would eventually journey thousands of miles from their native Austria to photograph that penguin –and more– on desolate Ross Island where British adventurers of another age had erected pre-fabricated buildings to serve as base camps and shelters from 1901–1917.

The huts, some of which provided quarters for as many as 25 men for several years at a time, were well equipped and provisioned. One even had a fully functional darkroom. When the expeditions ended, the explorers left everything in place—even their toothbrushes. The penguin was about to be stuffed when the orders were given to move out.

Image © Josef Hoflehner

Today, the huts are still crammed with crates of butter and boxes of bullets, canned foods, preserved hams, medicines, bottles of spirits, sleds, skis, pony harnesses, tools, snowshoes for mules and more. A pan of chopped seal meat rests on a stove that will never again be lit.

In 2001 Hoflehner began to produce coffee-table books of his work. He sailed with his daughter, Katharina, on a cruise from New Zealand to Antarctica and gathered a collection of images that would later become the critically acclaimed book Southern Ocean

“When we visited Ross Island we had only a few minutes to have a look around inside two of the explorers’ huts,” he recalls, “but even this short period of time was long enough for me to become addicted to the idea of doing another book.”

Image © Josef Hoflehner

Back on the ship, he methodically searched its extensive Antarctic library for information about the huts. “There was nothing on these fascinating places,” he recalls. “Unbelievable! I remember I was so overwhelmed that I could not sleep that night and I planned to do something.”

When he returned to New Zealand, he swung into action to get clearance for himself and his daughter to visit and shoot at three sites: Hut Point, Cape Evans and Cape Royds. “The whole process of bureaucracy took several months,” he remembers, “but finally the permission was granted to go back to Antarctica the following year for the project.”

Then doubts began to set in. First, it would be expensive because he’d have to fund the entire project himself—costs of flights to and from Antarctica, accommodation, provisions, helicopter hours, a guide for two weeks and more. In retrospect, he says he is grateful it was possible at all. “I must say that I’m not one who asks for money. Every cent was fully financed by myself and if I can afford it, I do it. If not—not.”

Image © Josef Hoflehner

There were other concerns. The proposed book—Frozen History, The Legacy of Scott and Shackleton—would present huge technical and commercial challenges he wasn’t all that comfortable with. “I don’t need a new challenge each day but gradually I began to see this as an opportunity. Even though the commercial risk was 100%, the artistic risk was zero.”

That’s because these three photographically unexplored huts had played major roles in the heroic age of British Antarctic exploration, and all were virtually inaccessible to the camera’s eye due to their remoteness and deteriorating condition. Whoever documented them first would bring a treasure trove of images to a world that had mostly forgotten the superhuman endeavors of those early explorers and the extreme environmental conditions under which they labored.

So in 2002, Hoflehner and Katharina again jetted to New Zealand, where they stayed a few days at Scott Base to take safety-training instruction before taking a U.S. Air Force Hercules prop jet to Ross Island. Then they started photographing the first hut nearby. Later, they had to helicopter to the other two huts taking along tents, sleeping bags and supplies. “It was a very special experience in itself to camp within a short distance from the huts in the midst of breathtaking landscape,” Hoflehner recalls.

Image © Josef Hoflehner

The interiors of the huts were dark and very cold with soot-blackened walls and ceilings that sucked up most of the light that filtered in from small windows. For many of the shots, Hoflehner needed a flashlight to find focus. He had decided beforehand to use only natural light, which required a tripod and long exposure times (most were about 30 seconds at f/2.8 to f/5.6). “We wanted to produce photographs as pristine as possible that captured the atmosphere and the mood within these magic places,” he explains.

Their guide, Dr. David Harrowfield, an Antarctic conservationist, spent a week with Hoflehner and Katharina. Having assisted professional photographers on the icy continent for many years, he remembers Hoflehner as “particularly special.” He points out that on Scott’s second expedition in 1911 the official photographer, Herbert Ponting, described himself as a “camera artist.”

Image © Josef Hoflehner

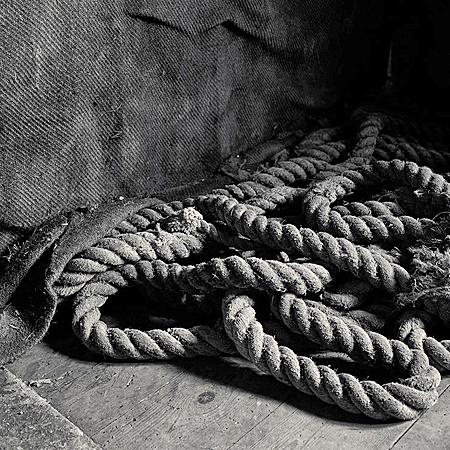

“I often wondered about this,” Harrowfield says, “and it was not until I observed Josef at work that I realized how appropriate the term was. A shaft of sunlight entering the hut would be used to [his] advantage and the artifact then assumed a significance of its own. Even a piece of frayed rope became a work of art.”

Hoflehner had first planned to use 4 x 5 film as he had done on his previous projects, but soon realized that this shoot called for an exception because “it was something special.” Digital had begun to prove itself and, for their interior images, he and Katharina used a Phase One H20 digital camera back on a TrueWide Digital sliding-back camera with Nikkor 17–35mm, 50mm and 85mm lenses. Film, though, was still his choice for exteriors—120 Kodak EPP (Ektachrome Plus Professional) and a Pentax 67II with 45mm and 105mm lenses, a Horseman 612 with a Rodenstock 45mm lens and a Fuji GX617 with 90mm and 180mm lenses.

Image © Josef Hoflehner

“Using digital was a tough decision,” he remembers, “but I still think it was the only way to go because in that kind of darkness, no light meter would give usable results and Polaroid wasn’t an option at freezing temperatures of 14 degrees F. Shooting the interiors was a once-in-a-lifetime project. There were a lot of images to take and time was limited. I would have no chance to re-shoot or check results by developing on-site.” In retrospect, he says he was pleased with the digital images’ wide dynamic range and lack of grain. It turns out that Hoflehner had captured an otherworldly series of timeless still-lifes that spoke to both the eye and the soul.

Once back in Austria the real work began for, as Hoflehner says, wryly, “Photography was only one part of the project and for me the simplest one.” He began to gather information to flesh out the book so the pictures could be viewed in context with the times. That meant combing libraries for quotes from the men who had lived in the huts and getting permission to use them. Then came the layout and prepress and finally, Hoflehner says proudly, “the first and only detailed documentation on the three historic huts on Ross Island, about a hundred years after their construction.”

Image © Josef Hoflehner

Since Frozen History was published he has gone on to publish more than a dozen books, many of which are still in print and available for sale. He says it turned out to be a good idea to start self-publishing his work. “Some say producing photography books is a wonderful way to burn money. Granted, it is a tiny market and they are expensive to produce, but it is interesting work and a nice marketing tool because the book is more or less a byproduct of the images, which are sold at galleries and elsewhere. I make a good living at it and it gives me a chance to travel and control my own destiny.”

Sometimes he even goes back to places during different seasons and, as he takes more images, the concept begins to evolve further and become clearer. “I must say that I don’t take it easy and I really try to produce strong images during these stages. At the end, I’m pretty demanding and I don’t accept average work. If I feel it’s not strong enough, I’d better leave it.”

Image © Josef Hoflehner

Hoflehner has completed multiple projects since Frozen in Time and most of his books are still available from him, Amazon and other sources. Prints in various sizes can also be purchased. Now 67, he reflects on his career that has spanned more than five decades:

“Shortly after I came in touch with photography, it became my passion and still is. Photography is my life and even after all these years, I’m not tired or bored. I cannot imagine working at anything else.”

RESOURCES:

See more of Josef Hoflehner’s work at www.josefhoflehner.com.

See many more images from Frozen History here.

He can be contacted at [email protected].

Original Publication Date: May 21, 2023

Article Last updated: May 17, 2024

Related Posts and Information

Categories

About Photographers

Announcements

Back to Basics

Books and Videos

Cards and Calendars

Commentary

Contests

Displaying Images

Editing for Print

Events

Favorite Photo Locations

Featured Software

Free Stuff

Handy Hardware

How-To-Do-It

Imaging

Inks and Papers

Marketing Images

Monitors

Odds and Ends

Photo Gear and Services

Photo History

Photography

Printer Reviews

Printing

Printing Project Ideas

Red River Paper

Red River Paper Pro

RRP Products

Scanners and Scanning

Success on Paper

Techniques

Techniques

Tips and Tricks

Webinars

Words from the Web

Workshops and Exhibits

all

Archives

January, 2025

December, 2024

November, 2024

October, 2024

September, 2024

August, 2024

July, 2024

June, 2024

May, 2024

more archive dates

archive article list