Julia Margaret Cameron: Breaking the Mold of Victorian Photography

Athough only a professional photographer for 11 years, her work was groundbreaking. When she died at 63, she'd left a legacy of more than 900 innovative portraits of England's Victorians.

By SHONA PARKER

No sooner had Queen Victoria ascended to the throne of Great Britain in 1837 than the new art of photography started to record images from an age of art, science and invention.

By 1851, the Great Exhibition in London was able to showcase a mixture of approximately 700 daguerreotypes, calotypes and stereo cards as well as photographic equipment in use. Reports of the exhibition published afterwards included plates of photographs detailing the selection of exhibits.

Early practitioners of photography were a mixture of scientist and artist, striving for a clean and clear image of the subject which was perfectly balanced against the background but with the right amount of light captured and an overall air of nobility and elegance to the whole portrait. The photographic studio portrait quickly became big business as the middle classes embraced the efficiency and the affordability of the photograph. In 1851, there were 12 photographic studios in London; by 1866 there were 254.

Julia Margaret Cameron, 1870

Photography was at first the preserve of the elite. The equipment was large, bulky and expensive and taking a photograph was a time consuming business. Only those who had an alternative income could afford to spend the time and money experimenting with this new invention. And it was one such person, Julia Margaret Cameron, who took this new invention and showed how, with the right handling and imagination, photography could produce contemporary art to rival that of the old masters.

Born in Calcutta, in 1815, Julia Margaret Pattle and her numerous siblings had a privileged upbringing. Her mother, born of French aristocracy and father, an East India Company official, led an idyllic and artistic if somewhat eccentric life. Julia herself was educated in France. When she married her husband, Charles Hay Cameron in 1838, Julia immersed herself in colonial life, establishing herself as a prominent hostess with enthusiasm and alacrity.Julia Margaret Cameron 1870

Ten years later, Julia and Charles moved to England. Several of Julia’s sisters had already settled in London and the Camerons joined their circle of literary and artistic friends. Julia had already become acquainted with the British astronomer John Herschel whilst in South Africa, where he introduced her to photography in 1842. But it was when the Cameron’s decided to settle at Freshwater on the Isle of Wight in 1863 that her daughter gifted her with a camera because she felt it may “amuse you mother, to try to photograph during your solitude …”

Julia, whose many friends included Charles Darwin, Alfred Lord Tennyson and Robert Browning did more than “try to photograph”, she fully embraced the process. She knew she wasn’t a professional but she acted like one as she coerced family, servants and celebrity friends into posing for her portraits whilst she tried to convey spirituality, beauty and truth, eschewing the more fashionable art of portrait photography for pictures which “electrify you with delight and startle the world.”

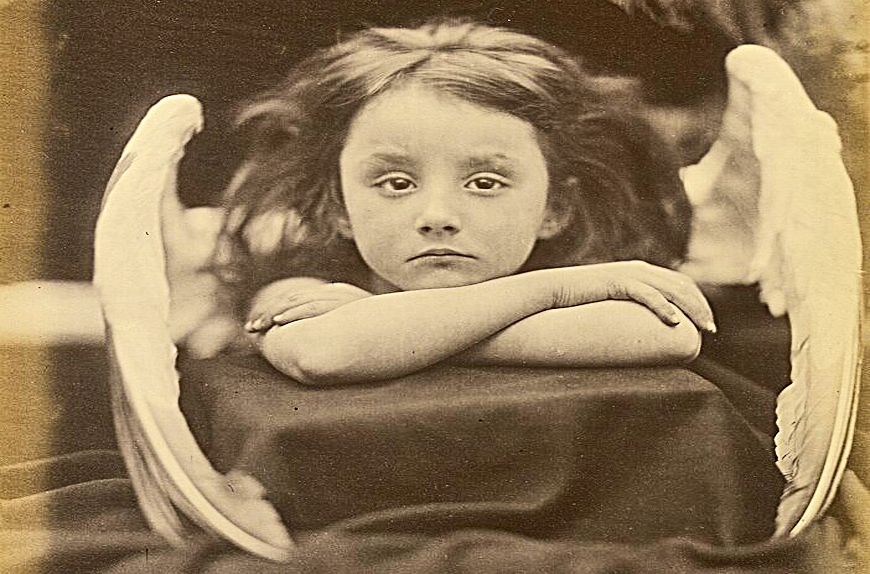

One month after receiving her camera, Julia captured the image of Annie Philpott, the daughter of friends on the Isle of Wight, in an albumen print from a wet collodion negative. Rather than sitting straight and formal as was the norm, Julia showed Annie as if she had just run up to the camera. Her hair is tousled and she appears to be about to speak to someone just outside the picture. There is a slight scruffiness to the photograph too, capturing the essence of what it is like to be a child. Julia was so thrilled with this image that she “ran all over the house to search for gifts for the child. I felt as if she entirely had made the picture.”

Annie Philpott, 1864

After this first success, Julia threw herself into her photography. She was 48 years old and the mother of 6 children but she didn’t let that deter her, neither did she balk at the messy chemicals and heavy, cumbersome equipment she had to use. She continued producing albumen prints from wet collodion glass negatives, as was standard practice at the time, but her actual compositions were anything but standard.

By 1865, Julia had progressed onto a larger camera which held 15 x 12-inch glass negatives. She used this to produce her emotional larger sized and close portraits. She was looking to go against the convention of distant portraits here, and mixed with her flaws in the negatives, Julia managed to create an ethereal, spiritual and artistic feel to her pictures, rather than concentrating on capturing exactly what the camera saw.

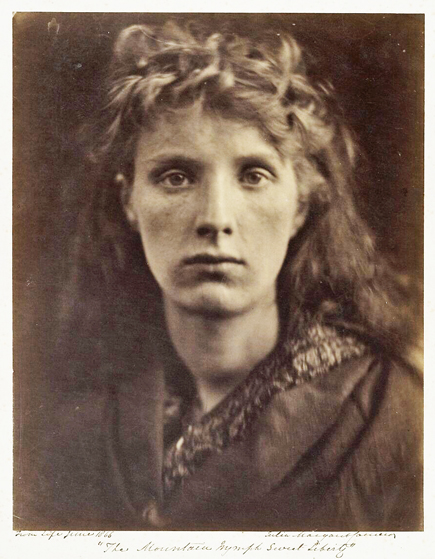

Julia enjoyed costuming her sitters and posing them to recreate mythical and biblical pictorial scenes. Her photographs mirror the romantic and Pre-Raphaelite paintings of the day, showing the human form in all its beauty. She gave her photographs appropriate artistic descriptions such as The Mountain Nymph Sweet Liberty from 1866 (below). We only know the model as Miss Keene but when he saw the photograph, John Herschel enthused over the way she fills the frame and that “she is absolutely alive and thrusting out her head from the paper into the air. This is your own special style."

The Mountain Nymph Sweet Liberty, 1866

It was very easy to make mistakes with this early form of photography as the perfectly clean glass plate was coated in fresh photosensitive chemicals whilst in a darkroom and then placed in the camera still damp. This meant it was open to collecting dust, hair, fingerprints and accidental smudges. Once exposed, the glass negative was taken back to the darkroom where it was developed. After being washed and varnished, the glass negative was placed onto sensitized photographic paper in direct sunlight and left to create a print. Only then would the smudges and blurs become apparent, but Julia accepted these all the same. In this photo of Alfred Lord Tennyson (below), he inadvertently moved as the picture was taken. Rather than destroy it because of this, Julia proudly displayed it because of the movement given to the portrait, something not embraced before in static images.

Alfred Lord Tennyson ,1864

Julia also experimented with soft focusing and engraving directly onto the glass negative to create hybrids of photography and illustration. Here, she photographed her niece Julia Jackson and drew in architecture and other detail to give the feel of religious iconography.

Julia Jackson, 1864

Julia broke ‘the rules’ of established photography with her usual enthusiasm and joie de vivre and it wasn’t long before she’d caught Henry Cole’s patronage. He was director of London’s South Kensington Museum (later renamed the Victorian and Albert Museum) and a supporter of photography as well as inventor of the Christmas card. This was the sole place which allowed her to exhibit her work, a remarkable feat for a woman too. At a time when female artists were not allowed to become members or train at the Royal Academy of Art, and exhibitions of their work were strictly limited, Julia was able to present to the public her photographic portraits in all their flawed glory.

In 1868, Julia was granted the use of two rooms at the museum where she operated a portrait studio, producing autographed photographs of her friends such as Charles Darwin to sell for profit. Despite this opportunity, she still lamented that “but even now after five years of toil, ardent patient persisting toil I have not yet by one Hundred Pounds recovered the money I have spent.”

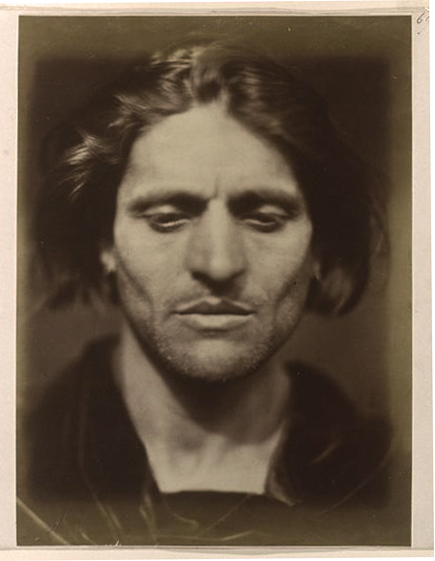

Julia spent eleven years producing pictorial effects and portraits of the great and good literary folk and artists of the time, as well as photographing some beautiful models and presenting them as characters from Greek and Shakespeare plays such as Iago below:

Iago, 1867

The Camerons eventually moved to Ceylon in 1875 to be nearer their sons and Julia’s artistic output slowed considerably as she helped to run the family's coffee plantations and look after her grandchildren. Four years later, after a short illness, she died at the age of 63. Although she may have spent only 11 years as a photographer, Julia blazed a trail of inspiration; not only for female photographers but for the art form itself.

She lit up the world of photography with her imagination, artistry and professionalism, producing about 900 extraordinary photographs, most of which are in the collection of the prestigious Victoria and Albert Museum.

About The Author:

Shona Parker is a lover and writer of English social history with a penchant for museums, castles, large gardens and copious amounts of tea and cake. She is happiest when falling down research rabbit holes. Her first book, How the Victorians Lived, was published by history specialists Pen and Sword Books in June 2024 and she is now in the midst of writing a follow-up.

RESOURCES:

Visit Shona’s website for history articles and information. You can also find her on X: @_backinthedayof

At the website of the Vuctoria and Albert Museum you can view videos, articles and more of Julia’Margaret Cameron's ground breaking photographs.

Shona's book, How The Victorians Lived is available on Amazon in hardcover ($37) or Kindle ($27).

Original Publication Date: February 01, 2025

Article Last updated: February 02, 2025

Related Posts and Information

Categories

About Photographers

Announcements

Back to Basics

Books and Videos

Cards and Calendars

Commentary

Contests

Displaying Images

Editing for Print

Events

Favorite Photo Locations

Featured Software

Free Stuff

Handy Hardware

How-To-Do-It

Imaging

Inks and Papers

Marketing Images

Monitors

Odds and Ends

Photo Gear and Services

Photo History

Photography

Printer Reviews

Printing

Printing Project Ideas

Red River Paper

Red River Paper Pro

RRP Products

Scanners and Scanning

Success on Paper

Techniques

Techniques

Tips and Tricks

Webinars

Words from the Web

Workshops and Exhibits

all

Archives

January, 2025

December, 2024

November, 2024

October, 2024

September, 2024

August, 2024

July, 2024

June, 2024

May, 2024

more archive dates

archive article list