H. H. Bennett’s Shot That Changed Photography Forever

by ARTHUR H. BLEICH

It’s 1865. The Civil war has just ended and 22-year-old Henry Hamilton Bennett is facing a quandary.

The young Union Army veteran had enlisted in the Wisconsin Infantry, and, while fighting in the Battle of Vicksburg, was severely wounded when his own gun accidentally discharged, injuring his right hand. Returning to his pre-war job as a carpenter was now impossible.

Having always been interested in photography he and his new bride Francis (who he affectionately calls Frankie) decide to buy a photo studio in Kilbourn City, Wisconsin where Henry begins his career as a photographer. in a uniquely beautiful area of the state called the Wisconsin Dells, a scenic, glacial-formed gorge that features sandstone formations along the banks of the Wisconsin River about 40 miles north of Madison, the state’s capital.

At first there’s not much demand for studio portraits so Frankie learns photography and takes over that part of the business while Henry begins to roam the area creating 3-D landscape images that can be reproduced and be sold for viewing on the home stereoscopes of the day. The views begin sell, but more importantly, they begin to encourage tourists from all over the world to visit. The town is eventually renamed Wisconsin Dells.

Compared to today’s easy-to-use digital cameras (and even those that came before), capturing images in the mid 19th century was a hassle. Metal plates were usually coated with various chemicals in a darkroom to make them light-sensitive, placed in light-proof holders and were then were inserted into the camera. The next hurdle was to shoot the image while the plate was still moist or else it would lose its sensitivity to light.

An early photographer’s manual titled The Silver Sunbeam sheds some light on the process: “Place the cap on the lens; let the eyes of the sitter be directed to a given point; withdraw the ground glass slide; insert the plate-holder; raise or remove its slide; Attention! Remove the lens cap and count one, two, three, four, five, six! (slowly and deliberately pronounced in as many seconds either aloud or in spirit). Cover the lens. Down with the slide gently but with firmness. Withdraw the plate holder and yourself into the darkroom and shut the door.” In the time it’s taken you to read this, a plethora of images could be taken with most of today’s digital cameras.

But once again in the darkroom, the latent image on the plate had to be developed and made permanent in various solutions before it was offered to the customer. There were no negatives from which copies could be made; that came later. And in case you’re wondering, photographers who shot pictures away from their studios had to lug a heavy darkroom tent along with them.

Bennett soon found that landscapes were his passion and he left most of the studio portraiture work to Frankie while he traipsed around the area, darkroom in tow, shooting the Dells’ magnificent scenery and, occasionally, portraits of a nearby Native American tribe. He lamented that sometimes shots of dark scenery required exposures of one-and-half hours. Still, as he once told a friend, “ You don’t have to pose nature and it is less trouble to please.”

In 1871 a cataclysmic change rocked the photographic world with the invention of the Gelatin or Dry Plate process that eliminated the need for photographers to pre-coat their own plates with wet chemicals in a darkroom. They could now be purchased pre-coated with a dried, light-sensitive gelatin emulsion that made them easy to ship anywhere in the world.

As with anything new, they were scorned by purists who complained they were not as sharp as traditional wet plates, but aside from being dry, the had the additional advantage of greatly increased sensitivity to light. Exposures could be made in fractions of seconds instead of seconds, minutes, or even hours. Bennett quickly realized this that despite his initial misgivings about them, their advantage was indisputable. He could now take “instant” photos. But how he had to figure a way to regulate the shorter exposure times that would be required. Enter “The Snapper.”

Always mechanically inclined (he had built his own cameras at times) he set to work and came up with a contraption made of rubber bands and other materials that would take the place of a lens cap and was be affixed in front of the lens allowing light top enter the camera by opening and closing at various speeds.

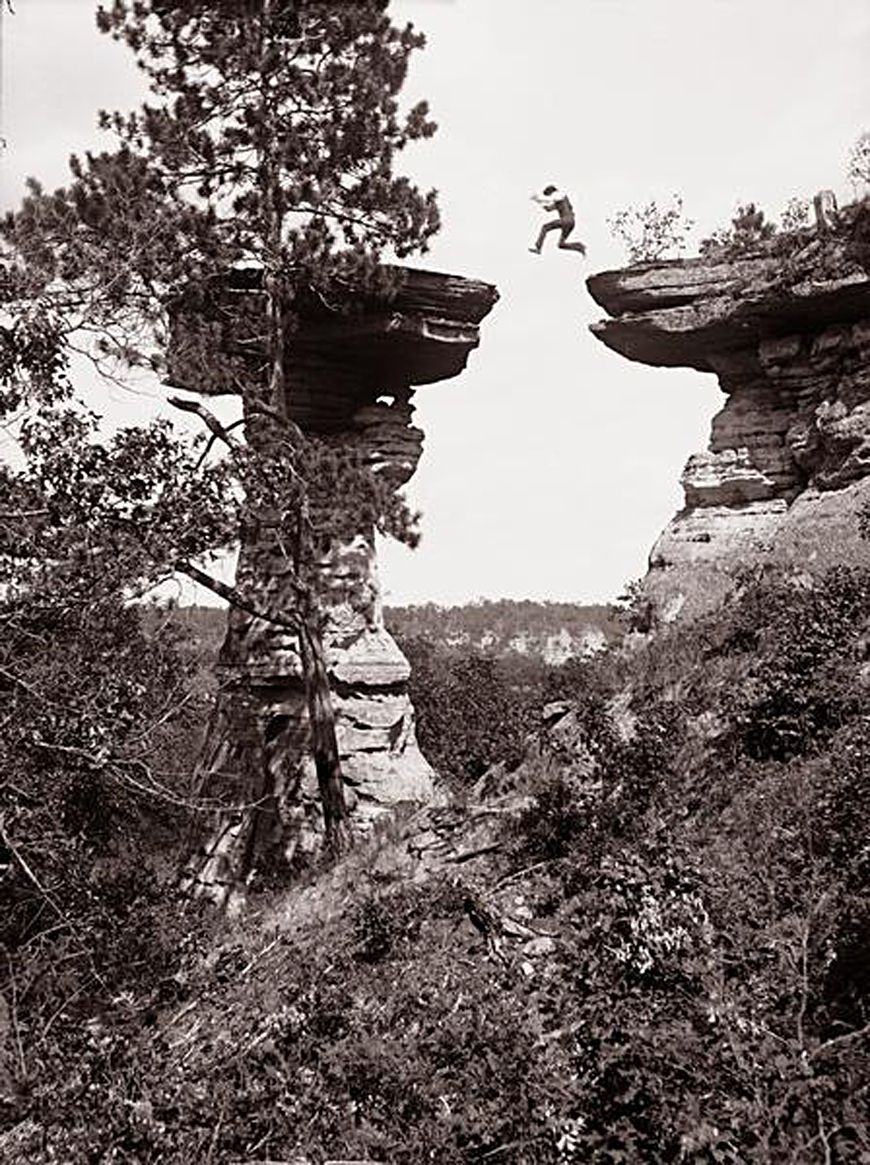

On a clear day in 1886, he asked his 17-year-old son, Ashley, to make a 5 -1/2 foot leap from the top of one of one rock formation to another. Ashley repeated it more than a dozen times until his father was satisfied that he had captured the young man in mid air at just the right spot. When he had developed the dry plates, Bennett was delighted. He’d created an image that would be seen around the world as a breakthrough in photography.

At first, other photographers scoffed at the image, declaring it a fake because it was common at the time for photographers to “improve” their work with special effects. Clouds for example were often added since films at that time were not sensitive to blue, and skies were usually “bald.” The suspicion soon faded, though, when Bennett began to freeze other subjects and objects in motion.Eventually, other more sophisticated shutter mechanisms evolved that were mounted behind the lensor even between lens elements that made and stopping action commonplace.

Toward the end of the century tourists who could now buy more technically advanced cameras tried to imitate Bennett’s shot. But after several of them came to an unfortunate end, only park rangers were allowed to pose for the shot. But that, too, proved too dangerous and finally, a dog was trained to make the jump.

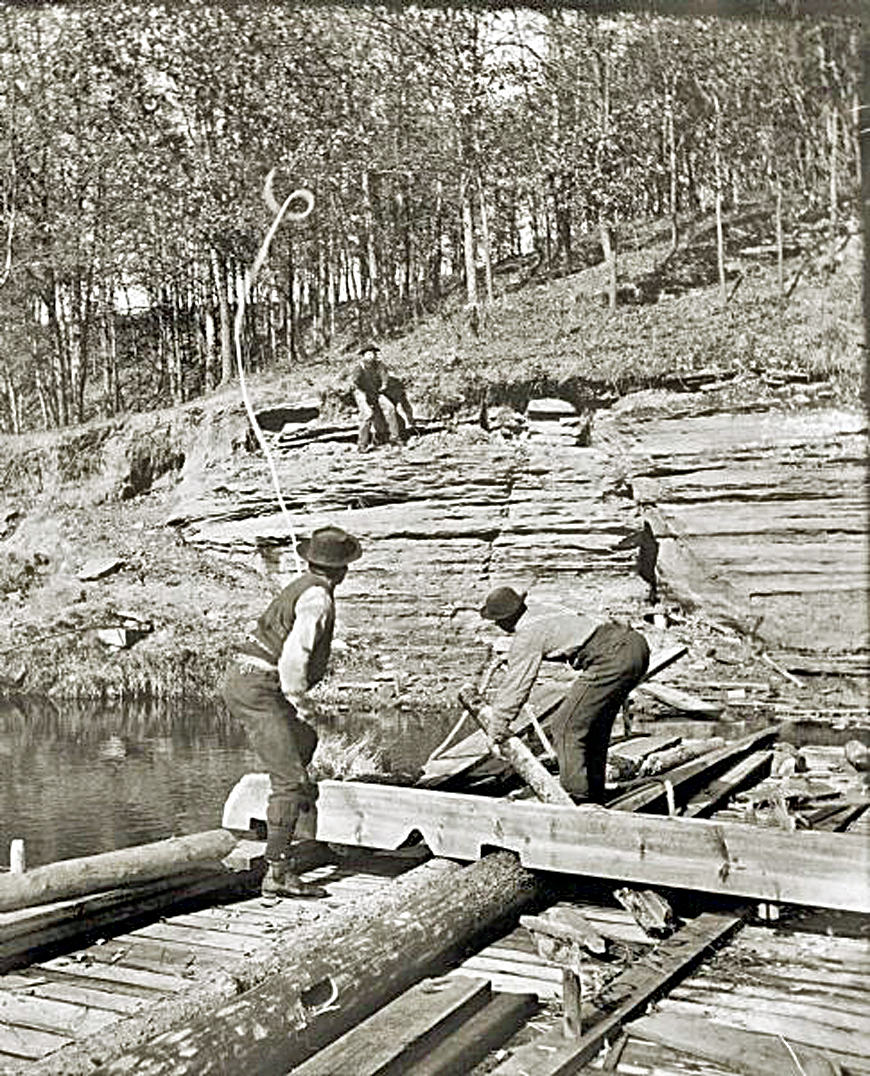

Once Bennett had perfected the Snapper, he, along with Ashley as his assistant, documented the life of a group of rivermen who floated log rafts down the Wisconsin River and shot about 40 images with his stereo camera during their trip, making it the first time that a sequence of images telling a story had been made. Many consider Bennett to be the father of photojournalism.

Today Wisconsin Dells, is home to several of the country’s biggest water park attractions along with several theme parks. Mirror Lake State Park, a forested reserve is known for its nature trails and camping. The scenery is still stunning and Bennett’s Photography Studio And Museum is open to the public where they can have an old time wet plate portrait taken, and view his photographic equipment along with many of the beautiful images he made.

RESOURCES:

See more of Bennett's photography

H.H. Bennett Studio And Museum

Original Publication Date: December 07, 2024

Article Last updated: December 18, 2024

Related Posts and Information

Categories

About Photographers

Announcements

Back to Basics

Books and Videos

Cards and Calendars

Commentary

Contests

Displaying Images

Editing for Print

Events

Favorite Photo Locations

Featured Software

Free Stuff

Handy Hardware

How-To-Do-It

Imaging

Inks and Papers

Marketing Images

Monitors

Odds and Ends

Photo Gear and Services

Photo History

Photography

Printer Reviews

Printing

Printing Project Ideas

Red River Paper

Red River Paper Pro

RRP Products

Scanners and Scanning

Success on Paper

Techniques

Techniques

Tips and Tricks

Webinars

Words from the Web

Workshops and Exhibits

all

Archives

January, 2025

December, 2024

November, 2024

October, 2024

September, 2024

August, 2024

July, 2024

June, 2024

May, 2024

more archive dates

archive article list